011 - Working with synthetic data

What we call synthetic data are data generated artificially, as opposed to data taken from real-life samples. In the case of automatic transcription or layout analysis, it corresponds to creating fake documents or samples of text that look more or less like real ones, in stead of manually annotating existing documents.

One of the main advantages of using synthetic data rather than real data is the fact that it comes already annotated. For automatic transcription for example, the annotation (transcription) is the same as the string of text passed to a text image generator. If you add to that the fact you can, in theory, generate an unlimited amount of pairs of text image and transcription, it represents an incredible opportunity to accelerate the production of training datasets. An example: Doush et al., 2018 use this technique to generate PDF containing contemporary printed Arabic texts. The PDFs are printed, then re-scanned and aligned with the transcription that was used to generate the PDFs. The result is the Yarmouk dataset. As we will see later, generating fake handwritten text is a bit more difficult.

Another advantage of this technique is that it offers an efficient way around the limitations posed by sensitive or confidential data (Hu et al. 2014). However, let's note that confidentiality is rarely a problem when it comes to training HTR models on historical documents.

Generating fake data is not specific to computer vision (Raghunathan, 2021), even though it is frequently used in this case because data for computer vision tasks are costly to produce. In general, it is a fairly frequent method when machine learning techniques are involved, disregarding the field of application (Kataoka et al., 2022). OCR and HTR tasks are not an exception and we can find traces of such experiments rather early (Beusekom et al., 2008).

The first time I was exposed to the notion of synthetic data was during a informal conversation with Tom Monnier in 2019. At that time, he was working on docExtractor, a layout analysis tool that he trained with images of documents generated artificially.1

Then sometimes in 2021, while browsing through HuggingFace's spaces, I found ntt123's application that simulates handwriting. The application takes a text prompt as an input and generates an animation where the letters are traced on the page as if someone was writing them live. It's possible to play with two parameters: a value between 0 and 250 determining the writing style, and a weight determining the likelihood of the traced letters (the lower the weight, the higher the risk of hallucinated letters; the higher the weight, the more standardized the tracing). It made me think back to my conversation with Tom Monnier and I wondered if it could be used to generate pairs of text and images.

At the beginning of the year, I dedicated a good part of my time to testing data generation tools I could find online, to see if they could be used to create a set of fake ground truth that I would use later, in other experiments. I will introduce the latter in a future post, so let's first focus on handwritten data generation.

When I dug a bit more around ntt123's application, I was confronted with two things:

- unfortunately, ntt123's application was developed in javascript and not documented at all which made it impossible for me to hack,

- but luckily, it wasn't an original idea: instead it was one of many implementations of a proposition introduced by Alex Graves in 2014.

Alex Graves uses online2 data from the IAM database (Liwicki & Bunke, 2005) and an LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) to train a model capable of generating series of coordinates that trace letters and words. Initially, the model simply generates random series of letters and words, but it is then improved to take into account a text prompt which forces the models to generate a specific series of letters. As described before, the model also takes a weight (or bias) which normalizes the likelihood of the letters' shape, and can take a "priming line": the image of a handwritten line, whose writing style the model will try to copy. Once the coordinates are generated (including key information such as "ends-of-stroke"), it is easy to place them in an SVG file and visualize the result, with or without animation.

There are many many implementations of Alex Graves's experiment because it was such an important publication to demonstrate the usefulness of LSTM models. Several can be found on Github if you search "Alex Graves". For my experiment, I didn't want to develop my own adaptation of such a model, but rather to use programs that were ready to be used. This is the reason why I didn't look for papers but instead for recent (or recently updated) repositories on Github. I focused on Python programs because I wanted to be able to understand how they were developed.

One very promising implementation of Alex Graves' proposition was Evgenii Dolotov's pytorch-handwriting-synthesis-toolkit. It came with pre-trained models, and a utility scripts to feed the program a text prompt and generate an image. I customized3 the program a bit to fix a few bugs and try to make it generate several lines maintaining the same handwriting.

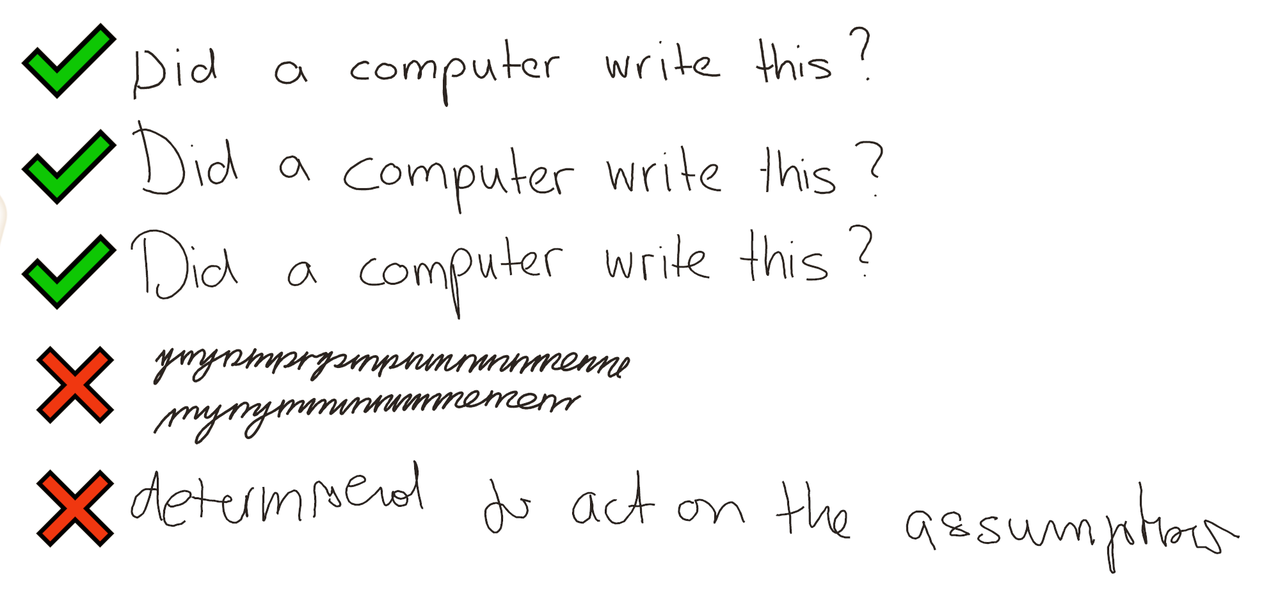

Even though the generated images were sometimes impressively realistic, it created a lot of bad output. As suggested by Alex Graves, his solution tends to generate what he calls "garbled letters", letters that no human would likely trace. In other cases, it would randomly skip some letters and be completely incapable of tracing some numbers or punctuation signs. Sometimes, the model would simply draw more or less flat lines. Since I wanted to generate fake gold data that I could trust and since the results were not reliable enough, I played with the bias and the priming lines before trying to train new models using Evgennii Dolotov's utility scripts. I failed to get better results than the pre-trained models, and failed to find the correct parameters to make sure I would obtain always realistic output.

At this point I started exploring GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) which are models based on game theory. They are capable of generating realistic fake images learning from samples of real images (see Goodfellow et al., 2020). They are this kind of models used to generate photos of people who don't exist. There are Github repositories offering source code to train such models to generate fake handwriting, such as GANwriting (described in Kang et al., 2020) or Amazon's ScrabbleGAN (introduced in Fogel et al., 2020) but they were only giving instructions to reproduce the corresponding papers and train the models ourselves. Since GANs are costly to train, I left this option out for the moment, even though I do think they can become an interesting solution in the future.

Eventually, I settled for a solution based on a Diffusion model. This type of model can be found behind applications like OpenAI's DALL-E. Luhman & Luhman (2020), who created the Diffusion Handwriting Generation (later called DHG), explain very well how diffusion models work.

"Diffusion probabilistic models [...] convert a known distribution (e.g. Gaussian) into a more complex data distribution. A diffusion process converts the data distribution into a simple distribution by iteratively adding Gaussian noise to the data, and the generative model learns to reverse this diffusion process." (Luhman & Luhman, 2020, p. 1)

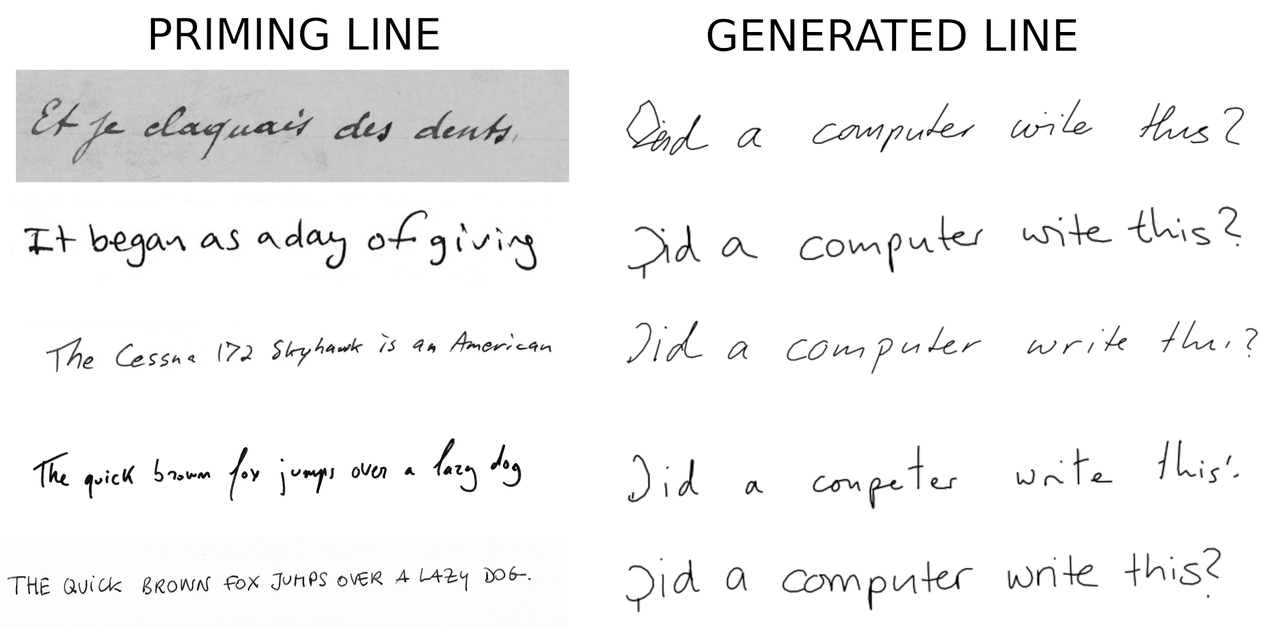

A great advantage with DHG compared to the LSTM approach was that it was possible to easily fix the priming line and almost always obtain a convincing output. This was essential to create a dataset with a consistent handwriting over hundred of lines. As visible in the following image, even if the diffusion model is not capable of perfectly imitating the handwriting contained in the priming line, it usually successfully captures elements of style such as the slant, or the cursive nature of the text.

After several tests, I found that the third priming line gave the best results when associated with different text prompts, so I decided to use it along with excerpts from Moby Dick to create a completely artificially generated dataset. In a few days, I created more than 8,000 images (PNG) associated with a text file (TXT) containing the prompts used to generate them.

These pairs could have been used "as is" to produce a silver synthetic dataset but, like I said before, I needed a gold dataset where the text and the images would be exact matches. Unfortunately, more than a third of the images did not qualify as gold. After manually reviewing about 2,500 of the lines (with the help of my colleague Hugo Scheithauer), we published a set of 1,280 pairs of lines and text under the name "Spinnerbait".

Even though I was able to produce a dataset meeting my main criteria, I was actually disappointed with my results: I wanted a sort of magic button which would allow me to generate, at any time and without having to review it, a perfect set of training data. Instead, in the future, if I want to add more lines to Spinnerbait, I will have to spend a few hours going through each line to filter the bad ones out.

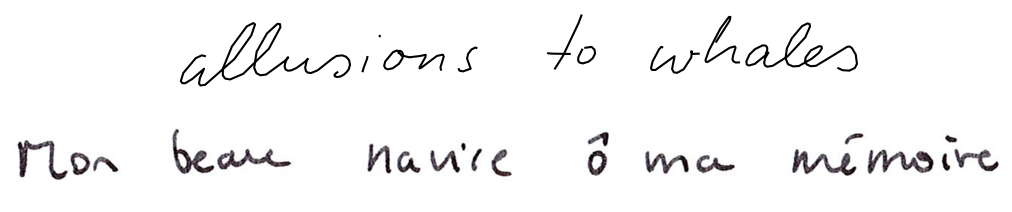

On the other hand, I decided to take a few hours to manually copy a text taken from Guillaume Apollinaire's poems. I copied the text following a txt file that I would edit every time I would start a new line, I scanned it, segmented it with eScriptorium before copying and pasting the lines from the txt file and exported the result as a series of XML ALTO and images. It gave birth to the Moonshines dataset, a set of 1,186 lines (including 170 dedicated to a fixed test subset) of a single hand, thus comparable in size to Spinnerbaits.

I think generating both datasets took about the same amount of time, if I take into account on the one hand reviewing the generated lines and on the other hand copying the text and passing it through eScriptorium. Moonshines used less computing resources and produced a richer dataset if we consider the aspect of the text. Also, the length of the lines is more varied in Moonshines whereas it is more homogenous (max 5 words) in Spinnerbait, because the generator tended to make more errors on longer prompts.

Another important limitation that I have barely addressed at this point it that not only do these tools fail to draw non-ASCII characters, but they also tend to have a greater chance of producing garbled letters when prompted with rare or non-english words4. This is true of all the systems I have tested. Of course, we could imagine training new models on data containing a greater diversity of languages, or simply other scripts or languages.

As way of a conclusion, I would say that even though I was disappointed with what I obtained down the line, this exploratory adventure was very interesting. I learned a lot and I am convinced that if I had more time and resources (and if it were more crucial for me), I would have found a way to get better results. I know of some coming publications that used GANs to create artificial data that look like lines taken from historical documents and I really look forward reading them.

-

It is possible to find here a recording of the talk given on this tool at ICFHR 2020. ↩

-

In the context of handwritten text recognition, a distinction is made between "online" data and "offline" data. Offline data are based on a matrix of pixels containing the image of a text (they are static), whereas online data are vectors containing information about the speed, the points through which a line passes to form a letter, end of stroke points, etc. Online HTR uses data generated with an e-pen and a screen while offline HTR uses images created with a scanner or a camera. ↩

-

One of the customizations consisted in removing non-ASCII characters or characters not supported by the model. It was easy to apply this transformation because in pytorch-handwriting-synthesis-toolkit, each model comes with a little metadata file which contains the character set handled by the model. ↩

-

All the models were trained using the IAM database, more often the "online" database, but sometimes also with the "offline" version. ↩